Vulnerability, Resiliency, and Adaptation: The Health of Latin Americans during the Migration Process to the United States

Vol.3 Núm.2 Vulnerability, Resiliency, and Adaptatio…

|

|

|

In this paper, we offer a general outlook of the health of Latin Americans (with a special emphasis on Mexicans) during the different stages of the migration process to the U.S. given the usefulness of the social vulnerability concept and given that said vulnerability varies conspicuously across the different stages of the migration process. Severe migrant vulnerability during the transit and crossing has serious negative health consequences. Yet, upon their arrival to the U.S., migrant health is favorable in outcomes such as mortality by many causes of death and in several chronic conditions and risk factors, though these apparent advantages seem to disappear during the process of adaptation to the host society. We discuss potential explanations for the initial health advantage and the sources of vulnerability that explain its erosion, with special emphasis in systematic timely access to health care. Given that migration can affect social vulnerability processes in sending areas, we discuss the potential health consequences for these places and conclude by considering the immigration and health policy implications of these issues for the United States and sending countries, with emphasis on Mexico.

Key words: social vulnerability, health, international migration, health care, legal status.

|

Ofrecemos un panorama del estado de salud de los migrantes latinoamericanos (con énfasis en los mexicanos) durante el proceso de migración a Estados Unidos de América (EE.UU.) desde la perspectiva de vulnerabilidad social dada la utilidad del concepto para el estudio del bienestar de los migrantes y la variación sustancial en las condiciones que afectan el bienestar de aquéllos en las distintas etapas del proceso migratorio. La alta vulnerabilidad de los migrantes durante el tránsito y cruce tiene varios efectos negativos en salud. A su llegada a EE.UU., dicha salud es empero favorable en mortalidad por varias causas y enfermedades crónicas, así como sus factores de riesgo más importantes. Sin embargo, estas ventajas desaparecen en el proceso de adaptación en el país de destino. Discutimos algunas de las explicaciones de las ventajas de salud y las fuentes de vulnerabilidad que describen la deterioración de dichas ventajas, en especial aquellas que operan a través de su acceso sistemático y oportuno a servicios de salud. Dado que la migración puede afectar la vulnerabilidad social en las áreas de origen de los migrantes, tratamos asimismo las consecuencias de salud de estos procesos. Concluimos con implicaciones de política migratoria y de salud para el contexto estadounidense y de países de origen con énfasis en el caso mexicano. Palabras clave: vulnerabilidad social, salud, migración internacional, servicios de salud, estatus legal. |

People face potential threats to their security, human rights, and health when they lack personal, social, and legal resources to face and prevent adverse social, economic, and environmental conditions, a phenomenon scholars call social vulnerability (Adger 2006; de Snyder et al. 2007). Individuals and social systems adapt to these adverse conditions by mitigating, preventing, or adapting to this harm in different ways. Geographic mobility is a common adaptation strategy to different sorts of social vulnerability (Bardsley and Hugo 2010). People migrate (oftentimes temporarily) in order to find better circumstances that allow them to alleviate the worst effects of social vulnerability in the short term or remedy them in the long run, not the least by allowing them to live in more secure, stable, and salubrious environments.

This kind of motivation may be more likely in the context of international migration as places of destination tend to have substantially better living and working conditions than sending areas. In addition to the sheer fact that migration allows people to improve their living situation by changing locales, migrants may also be able to save larger amounts of money they can devote to improving their living standards (e.g., Lindstrom 1996) and, even, to mitigate their degree of vulnerability in their places of origin (e.g., by allowing them to purchase capital goods and technology that will decrease their vulnerability to climatic events).

Despite its potential to alleviate certain forms of social vulnerability for migrants themselves and, more generally, for people in sending areas, the act of migration and the accompanying move into new social, economic, and legal milieu can also create additional forms of social vulnerability affecting their well-being, including their physical and mental health. U.S.-bound migrants and immigrants from Latin America have been depicted as vulnerable subjects due to their socioeconomic and legal status (Castillo 2000; Menjívar 2000; Téllez and Peña 2007). This vulnerability has health consequences, which are particularly severe, for instance, among people attempting to cross into the United States without documents due to extremely harsh conditions during the crossing, leading to substantial mortality hazards (e.g., Eschbach et al. 1999).

These sources of vulnerability (and, as we show below, their health consequences) vary considerably before, during, and after the migration process (also see Salgado de Snyder et al. 2007). As such, it is important to understand the consequences of social vulnerability on migrant well-being across these different stages. We focus on health in this paper as it is a key indicator of well-being and provide an overview of the health status of migrants along different stages of the migration process while identifying the main ways in which socioeconomic and legal vulnerability affect migrant health during each of these phases.

We begin by describing the negative health consequences of vulnerability experienced during the border-crossing process. We then provide a general overview of what seems to be a better than- expected migrant health in the United States (relative to U.S.-born individuals) while summarizing the main types of selection and protection mechanisms that have been advanced to explain this apparent resiliency. Further, we describe how the health of migrants changes (generally for the worse) through the process of adaptation to life in the U.S. and, we argue, due to the accumulation of stress related to the disadvantages faced by migrants during their U.S. experience. We discuss the role of legal and socioeconomic status in creating and compounding these disadvantages by disproportionately exposing migrants to risks that carry significant physical and mental health consequences (e.g., Kirschenbaum, Oigenblick and Goldberg 2000; Markides and Gerst 2011) and by hindering their access to systematic, timely, quality health care (Derose, Escarce and Lurie 2007). Finally, we discuss how the exchanges associated with the migration process might reduce or exacerbate vulnerability in sending communities. We conclude by discussing the health policy implications in the U.S. as well as in sending, transit, and destination countries. Given the relevance of the Mexican case (and our better knowledge of it relative to health policy in other Latin American nations), we focus our more specific conclusions on Mexico while attempting more general reflections that can be applicable to other sending nations.

Health and vulnerability throughout the migration process

The pitfalls of attempting to cross the border

Most notably, migrants are highly vulnerable to the dangers of crossing the border without documents. Although these dangers have existed in one way or another for as long as undocumented crossing has, they have increased over time as enforcement in high-transit urban border corridors escalated in the mid-1990s (Spener 2009). This enforcement pushed undocumented traffic to desolate areas, particularly in the Arizona portion of the Sonoran Desert, increasing the death toll from hyperthermia, dehydration, and heat stroke (Eschbach et al. 1999).

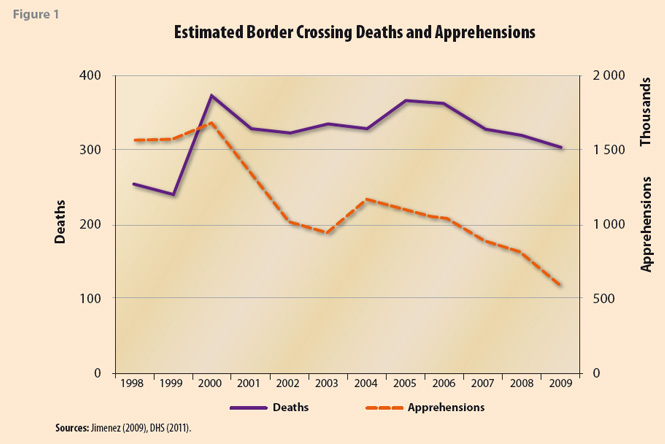

Although any reports are likely underestimates, between the mid-1990s and 2005 the annual border crossing deaths more than doubled to almost 500 (see Figure 1 below, also see GAO 2006) and have not decreased in recent times despite the decrease in undocumented crossings as a result of the most recent recession (Passel, Cohn and Gonzalez-Barrera 2012). As shown in Figure 1, while border apprehensions (a gross measure of the undocumented flow) decreased from a high point of almost 1.7 million in 2000 to a low point of less than 600 thousand in 2010 (a 65% reduction), border deaths went from a high point of 372 in 2000 to 304 in 2010 (a 17% reduction). It follows that the risk of crossing the border has in fact increased in recent years, assuming variation in apprehensions over time is similar to the fluctuation in attempted crossings.

Still, some of the worst dangers associated with undocumented migration are most likely faced south of the U.S.-Mexico border, particularly among Central, South American (and, in much lower numbers and more recently, Asian and African) migrants navigating Mexican territory without documents. Many migrants ride on top of northbound trains leaving from towns on the Southern Mexican border where they face the risk of injury and death from falling off moving trains (Nazario 2006). While traveling north, they also face the risk of violent robbery and sexual assault by marauders (Johnson 2008) or mistreatment and abuse by smugglers both on the Mexican and U.S. sides (Spener 2009).

In recent years, migrants have also been subjects of kidnapping, torture, and eventual death by members of criminal organizations (Casillas 2011). In the state of Tamaulipas mass graves were found in 2010 and 2011 with the bodies of around 130 migrants.1 It has also been reported that migrants face physical mistreatment by Mexican immigration authorities (Amnesty International 2010). At any rate and pending the details of (and probably despite the best intentions of) the new migration law in Mexico, migrants remain highly vulnerable in countries of transit (Bustamante 2011; Castillo 2000). Though it is hard to accurately assess the risk of injury and death during transit and even the crossing (despite the statistics shown above), the physical and mental health consequences are real and associated with the legal vulnerability of migrants, both in the U.S. and in Mexico.

While the crossing may be the stage in which migrants may be most vulnerable, different sources of vulnerability by which health can be affected do take place during the migration process, both in origin and destinations. Most of our knowledge of the potential effect in these sources lies in indirect evidence from studies looking at migrants once they make it to the United States. As such, we first discuss the findings of these studies while tracing how various conditions in migrant origins and destinations may be contributing to explain this state of affairs.

Migrant Health upon Arrival: The Hispanic Health Paradox

Despite the challenges faced at the border and (as we will see below) during the process of adaptation to U.S. society, many aspects of the health of Latin American migrants in the United States, particularly of those with shorter durations of stay, appear more favorable than those of other race/ethnic groups, including U.S.-born non-Hispanic (NH) whites. As higher socioeconomic status (SES) is generally associated with better health (Adler and Ostrove 1999) and Latin American migrants, particularly the recently-arrived, have below-average SES (Jiménez 2011), this phenomenon is thus commonly known as the Hispanic Health Paradox (HHP). The HHP is first and foremost apparent in adult mortality (Markides and Eschbach 2011) and is strongest among immigrants (Markides and Eschbach 2005), particularly those from Mexico, who have consistently lower mortality than U.S.-born NH whites (e.g. Palloni and Arias 2004). Singh and Hiatt (2006) estimate that life expectancy among Hispanic immigrants in 1999-2001 was 79.0 years for males and 84.1 years for females. Both figures are somewhat higher than those of U.S.-born NH whites at 74.8 for men and 79.9 years for women.

Scholars have been somewhat skeptical of these differences, pointing out they may be data errors related to the underestimation of migrant status among the deceased and other incongruences when calculating rates based on vital statistics (Eschbach, Kuo and Goodwin 2006), or to the disproportional mismatching of immigrants in mortality estimates coming from continuous surveys matched to the National Death Index (Patel et al. 2004). Despite the fact that these problems do lower immigrant mortality estimates, the general conclusion from studies assessing the HHP is that these biases do not entirely explain the immigrant mortality advantage (Markides and Eschbach 2005, 2011).

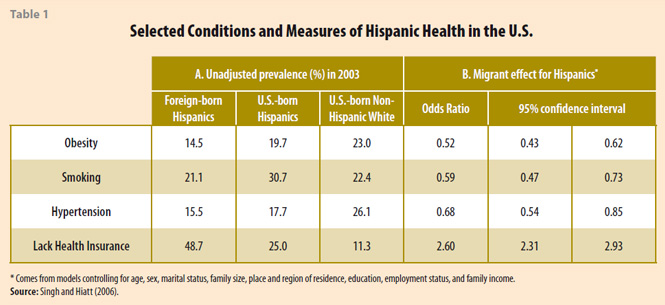

Better-than-expected survival must thus derive from a relatively favorable morbidity and associated risk factor profile among migrants. Although this is certainly not the case for many health conditions, studies have confirmed this notion for several health outcomes (see Table 1 below, for a review and meta-study see Cunningham, Ruben and Narayan 2008). Most notably, the foreign-born exhibit higher freedom from various chronic conditions (Singh and Siahpush 2002), hypertension in particular (Singh and Siahpush 2002) along with some types of cancer (Eschbach, Mahnken and Goodwin 2005). Immigrants also tend to exhibit a lower prevalence of smoking (Singh and Siahpush 2002) and obesity (Singh and Hiatt 2006).

This is illustrated in Table 1 using estimates from Singh and Hiatt (2006). Hispanic immigrants have a lower prevalence of obesity (15%), smoking (21%), and hypertension (16%) than U.S.-born non-Hispanic whites at 20%, 31%, and 18% respectively (see Panel A). These differences are not solely explained by the less favorable socioeconomic conditions in which migrants live. After controlling for several socio-demographic and economic factors, Hispanic immigrants have 48%, 41%, and 32% lower odds of reporting obesity, smoking, and hypertension than non-Hispanic whites, although they have 2.6 times higher odds of lacking health insurance (Panel B).

Thus, immigrants may be resilient to social vulnerability, at least upon arrival to the United States and despite their lack of health insurance coverage. However, note that the migrant community in the United States also experiences several health problems, many associated with different sources of social vulnerability. Migrant men tend to experience higher risks of HIV infection (Martínez-Donate et al. 2005), partly related to risky sexual behavior following family separation, precisely due to their (solo) migration (Parrado, Flippen and McQuiston 2004). In addition, the prevalence of diabetes is relatively high in migrant communities (Beard et al. 2009) as it is in many Latin American countries (Palloni et al. 2006).

Migrants from Latin America also disproportionately work in dangerous occupations (Orrenius and Zavodny 2009),2 resulting in higher rates of workrelated accidents and deaths (Kirschenbaum et al. 2000). For instance, Orrenius and Zavodny (2009) find that immigrants are more likely to experience work-related sprains and strains, fractures, cuts and punctures, bruises, chemical burns, heat burns, amputations, carpal tunnel syndrome, tendinitis, multiple traumatic injuries, pain, back pain, and other injuries than natives (p. 546). While literacy, schooling levels, and English ability explained away the differences in many (but not all) of these rates, some of these are in fact indicators of inadequate working conditions for immigrants (for an ethnographic account in the poultry industry see, for instance, Griffith 2005).

The cumulative effects of repetitive manual work might explain why old-age disability rates are not lower among migrants relative to U.S.-born individuals (Eschbach et al. 2007; Markides and Gerst 2011; Markides et al. 2007). For instance, Markides and Gerst (2011: Figure 7.2.) estimate age-standardized disability rates for men older than 65 at almost 50% for foreign-born Mexicans (slightly lower for foreign-born Hispanics) in the U.S., a number somewhat higher than the 43% for U.S.- born non-Hispanic whites. As some scholars (Eschbach et al. 2007; Markides and Gerst 2011) have also pointed out, the combination of high old-age disability rates and relatively high life expectancy imply an extension of morbid life (e.g., years spent in disability, Eschbach et al. 2007).

Despite these negative results, the otherwise relatively advantageous health profile of Latin American migrants in the United States could be a result of selection or protection taking place at the time of emigration or in the United States. We discuss these in the context of social vulnerability as they could be alternative explanations of the existence of an immigrant advantage (e.g., due to errors or compositional distortions in the data) or could signal certain forms of resiliency to social vulnerability both related to the emigration (e.g., the reasons why people moved out of their communities in their first place) and directly caused by it (i.e., by the migrant condition).

Leaving in the First Place: Health Selection in Emigration

One possibility is that migrant health is advantageous in the U.S. in part due to positive emigration selection, a set of processes whereby good health is a direct cause (or, at least, a more indirect facilitator) of migration. Studies that have tried to measure emigration selection by comparing the health of migrants in the U.S. with that of nonmigrants in sending countries have found evidence consistent with a moderate degree of positive emigration selection (Barquera et al. 2008; Crimmins et al. 2005; Riosmena, Palloni and Wong Forthcoming-b; Rubalcava et al. 2008). For instance, Riosmena et al. (Forthcoming-b) find that Mexican older adults with prior U.S. experience (living in either the U.S. or Mexico at the time of the survey) have 35% and 64% lower odds of hypertension and reporting poor/fair global health respectively than individuals living in Mexico with no prior U.S. experience. However, Rubalcava et al. (2008) find more modest differences between individuals ages 15-29 migrating to the U.S. between survey waves and nonmigrants in several health indicators measured at baseline, leading them to conclude that their study finds “generally weak support for the healthy migrant hypothesis” (p. 81). As such, while migrants do tend to be healthier than nonmigrants that remained in sending communities, these differences are not very large and, thus, may not explain the full immigrant health advantage in the United States (also see Discussion in Riosmena et al. Forthcoming-b).

These findings suggest that migrants may be slightly more resilient or less exposed to the types of vulnerability affecting nonmigrants in sending areas (and as migration is not necessarily associated with higher poverty per se, Massey and Espinosa 1997) and may bring some questions to the notion that migrants are vulnerable subjects. However, as emigration selection is moderate and, as explained in more detail below, the immigrant advantage seems to wane throughout the migrant’s tenure in the United States, we do not think this paradoxical series of results contravene a large body of evidence documenting some of the social vulnerability resulting from a migrant in both transit (e.g., Castillo 2000) and destination (e.g., Menjivar 2006), or its health consequences. Rather, it qualifies this notion by suggesting that the composition of immigrants may help them be a bit resilient to some of these forms of vulnerability (or less vulnerable in some ways). As also detailed below when discussing sociocultural protection factors, the migrant community may contain forms of resiliency that help explain these results. Before that, however, we explain how (return) selection could be altering the composition of migrants in the United States and explain part of the observed immigrant advantage.

The “Salmon Bias”: The Return Migration of the Unhealthy?

Whether or not there is health selection in emigration, the immigrant advantage could be partially explained by negative health selection in return migration, better known as the “salmon bias.” The salmon bias is a statistical artifact that overstates the health of a particular immigrant cohort when researchers observe only those remaining in the host country as is the case of the vast majority of HHP studies. Studies directly testing for the salmon bias have generally found a moderate degree of return migration selection for older adults (Palloni and Arias 2004; Riosmena et al. Forthcoming-b; Turra and Elo 2008). For instance, in their study of older adult men, Riosmena et al. (Forthcoming-b) find that return migrants (with less than 15 years of U.S. experience) have 83%, 125%, and 472% higher odds of reporting hypertension, current smoking, and poor/fair global health (respectively) than individuals remaining in the U.S., though they are not unhealthier in terms, for instance, of diabetes or obesity.

Although some of the differences in health outcomes between return migrants and immigrants living in the U.S. found by Riosmena and colleagues are large, they also show that the salmon bias does not explain the immigrant health advantage in conditions such as hypertension and obesity. Further, they find that adjusting for return migration selection increases the immigrant health disadvantage in smoking and self-rated health (Riosmena et al. Forthcoming-b: Table 1), suggesting the salmon bias is overall moderate, as also suggested in mortality studies (Abraido-Lanza et al. 1999; Hummer et al. 2007; Turra and Elo 2008).

Even though the health disadvantage of return migrants is not too large and may indicate, prima facie, a statistical distortion more than a substantive explanation for the health advantage of immigrants in the United States, return migrants could be more vulnerable upon return than they were before leaving the sending community. At the very least, the slightly negative selection of individuals returning could signify challenges for health and health care provision in sending communities.

However, return migrants do not seem to be consistently unhealthy when compared to nonmigrants in the communities they return to (Crimmins et al. 2005: Table 4). As we discuss below, return migration and other exchanges associated with U.S. migration (e.g., remittances) might further change community health in sending areas for both good and worse. Before turning to this in the context of sources of vulnerability in sending areas, we discuss how likely it is that migrant health changes throughout the process of incorporation to U.S. society and identify some of the main sources of migrant vulnerability in the U.S.

The Health of Migrants in the United States: Initial Sociocultural Protection?

Sociocultural protective factors, originating either Palloni and Morenoff 2001) or origin (Landale et al. 2000) in the host (Landale, Oropesa and Gorman 2000; country, could also be enabling Latin American migrants to cope better with daily life and promoting better health, thus contributing to their relatively favorable health in the United States and proving a source of resiliency to other forms of migrant vulnerability, sketched in a separate section below. Migrant networks, which tend to be instrumental in facilitating migration (Curran and Rivero-Fuentes 2003) and adaptation to the new setting (Munshi 2003) could also be providing support and protection to migrants beyond what the average nonmigrant gets. This support would then allow migrants to have more favorable health outcomes or behaviors in the U.S. compared to their pre-migration health.

As support networks may be clustered in space (e.g., operate in neighborhoods and communities), protection processes would likely be apparent when looking at spatial patterns of health among migrants, favoring those living in more tightly-knit neighborhoods and communities. Consistent with this notion, several studies have found better health outcomes among Latinos living in neighborhoods with higher concentrations of co-ethnics compared to those living elsewhere. Latino neighborhood concentration/segregation is negatively associated with mortality (Eschbach et al. 2004), cancer (Eschbach et al. 2005), depressive symptoms (Ostir et al. 2003), and self-rated health (but see Mulvaney-Day, Alegría and Sribney 2007; Patel et al. 2003). This is further seen as evidence of protection among the ethnic community given that people living in these neighborhoods have lower average socioeconomic status and relatively poor amenities and, as such, are expected to have worse health outcomes (e.g., Lee and Ferraro 2007).

However, these studies do not provide direct evidence of protection among the foreign-born as they did not distinguish if the so-called barrio effect was beneficial in the same way for immigrants and the U.S.-born. The evidence from studies that have made this distinction or that have looked exclusively at foreign-born Latinos is mixed (compare Cagney, Browning and Wallace 2007; Lee and Ferraro 2007), though studies testing for protection in other ways find some support for this idea among immigrant populations (Landale et al. 2000; Teitler, Hutto and Reichman 2012) (but see Riosmena et al. Forthcoming-b). Given that studies looking at both U.S.-born Hispanics seem overall more supportive of socio-cultural protection and one that examined U.S.- and foreign-born groups separately found more support for the U.S.-born (Lee and Ferraro 2007), we tentatively conclude that the ethnic community may be protecting U.S.-born Latinos more extensively than it protects migrants for some reason. However, more research is needed to fully evaluate this statement and understand these differences.

Health Trajectories of Migrants in the United States: Negative Acculturation and Cumulative Disadvantage

While the extent of sociocultural protection is not yet fully clear, immigrants do become more vulnerable in some ways over time spent in the United States and with increasing acculturation. Despite the average immigrant health advantage discussed above, the health of Latin American immigrants also seems to worsen with their increasing experience in the United States and, more specifically, with measures indicating an increasing adaptation to the prevalent values, customs, and behaviors of the host society, a process labeled acculturation. Duration and acculturation measures are positively correlated with lower consumption of fruit, vegetables, and fiber, and with other sorts of dietary changes generally regarded as unfavorable (Akresh 2007). Most likely as a result of these changes, these measures are also associated with higher body mass and obesity levels (Abraído- Lanza, Chao and Flórez 2005; Akresh 2007). Smoking prevalence and alcohol use (Abraído-Lanza et al. 2005; Lopez-Gonzalez, Aravena and Hummer 2005) also rise with duration in the United States, as do disability rates (Singh and Miller 2004; Singh and Siahpush 2002), chronic disease prevalence (Gorman and Read 2006; Singh and Miller 2004; Singh and Siahpush 2002), and mortality (Angel et al. 2010; Colón-López et al. 2009; Riosmena et al. 2011).3

Given that many of these studies use acculturation scales to measure the degree of immigrant “exposure” to U.S. society, these results overall are known as the Negative Acculturation hypothesis (Lara et al. 2005). These findings are paradoxical given that migrants come to the U.S. in the first place to improve their standards of living and those of their offspring, and that culturally “assimilating” into the mainstream should be a signal of the blurring of racial and ethnic boundaries (Alba and Nee 2003) that, in turn, should be accompanied by favorable structural changes (Rumbaut 1997).

Yet, a simple negative acculturation story would imply that the adoption of negative health behaviors by immigrants, interpreted by some as the (sole) result of individuals choices (as opposed to the result of choices made in the context of structural constraints potentially resulting from social vulnerability), translates into worse chronic health and higher mortality. Although this is indeed a likely pathway that could partially explain the negative association between exposure/acculturation measures and chronic health conditions, it is also likely that both acculturation and duration of stay measures are proxies for a more general kind of exposure to unfavorable living and working conditions, which may negatively impact chronic health (Abraído-Lanza et al. 2006).

As mentioned above when discussing outcomes where immigrants do not have a health advantage in the United States, these exposures may accumulate through life and affect health, disability, and survival. As such, it is relevant to consider how different sources of vulnerability associated with being a migrant or that are higher among migrants may increase their exposure to risks carrying significant physical and mental health consequences and hinder their access to systematic, timely, quality health care (Derose et al. 2007).

Main sources of migrant vulnerability in host and sending country

Thus far, we have provided a mixed picture of the health status of migrants throughout the process of getting to, returning from, and adapting to life in the United States: migrants are highly vulnerable in terms of health during the undocumented crossing; after arriving in somewhat good health in some indicators due to the combination of (modest) emigration and return selection migration processes (as well as data errors and, perhaps, a moderate degree of sociocultural protection), the (cumulative) results of their social vulnerability seem to show with increasing experience in the United States, as indicated by the worse health outcomes of more experienced immigrants. While migrant vulnerability during the crossing is clearly rooted in the lack of legal status in transit and destination countries, there are different ways in which legal and socioeconomic status act as the main sources of vulnerability migrants face in the United States. In addition to discussing these next, we also underscore that the act of migration might not only be accompanied by the creation of new sources of vulnerability (and the elimination of others) for migrants themselves, but that the translocal exchanges associated with U.S. migration might also increase or reduce these kinds of vulnerability for nonmigrants in sending areas.

Sources of Migrant Vulnerability in the United States

Socioeconomic and legal status are the two main sources of vulnerability affecting how migrant health changes with increasing experience to U.S. society. Latin American migrants have relatively low socioeconomic position relative to other race/ ethnic groups in measures such as schooling, occupational prestige, income, poverty status, and home ownership (Jiménez 2011). Although this situation tends to be better for people who arrived to the United States at younger ages, it is only substantial in measures of more extreme poverty (Myers, Gao and Emeka 2009: Figure 1).

Part of the socioeconomic disadvantage of migrants is of course related to the low human and financial capital they come with from the sending country as well as lower schooling levels in many of these areas relative to the U.S. (and despite the fact that migrants tend to be positively selected in terms of schooling, Feliciano 2005). Yet, legal status further exacerbates this disadvantage by exerting a penalty on wages even among people with similar schooling levels and occupations (Hall, Greenman and Farkas 2010; Mukhopadhyay and Oxborrow 2012). For instance, Hall et al. (2010) find wage penalties of 17% and 9% for undocumented Mexican immigrant men and women (respectively) when compared to their Mexican legal immigrant peers. Further, Mukhopadhyay and Oxborrow (2012) find that the acquisition of a green card (among employer-sponsored immigrants) leads to a wage gain of almost USD$12,000 relative to legal migrants with temporary worker visas, suggesting that the lack of freedom to change jobs among legal migrants has a penalty. Further, it suggests that the situation of those with temporary forms of legal status (particularly those tied to a particular employer) is not necessarily more advantageous than for those with no documentation (see also Donato, Stainback and Bankston 2005).

The lack of (permanent) legal status also makes other forms of socioeconomic achievement much more costly or difficult.4 Most notably, legal status clearly structures the types of jobs migrants have access to, regardless of their skill or schooling levels (Akresh 2006). It also makes their access to college extremely costly in most U.S. states (as undocumented migrants are not eligible to instate tuition or any publicly-funded educational grants),5 and makes investment in financial institutions and homeownership hard or impossible. As such, legal status compounds the typical socioeconomic disadvantage that immigrants may have due to the capital they bring with them.

The combination of low socioeconomic position and inexistent/gray legal statuses affect migrant health in two fundamental ways. First, it overly exposes migrants to different sorts of health risks. As mentioned in the outset, Latin American migrants are more likely to work in dangerous occupations (Orrenius and Zavodny 2009). Their apparent lack of labor protection6 also makes both undocumented and some types of documented workers more vulnerable to experience worse working conditions and dangerous workplaces (e.g., Donato et al. 2005; Griffith 2005). The occupational composition and poorer working conditions of migrants seem to translate into higher rates of work-related accidents (Kirschenbaum et al. 2000). Eventually, the cumulative effects of repetitive manual work in general and these kinds of experience in particular might be a conduit of the higher old-age disability rates among migrants relative to U.S.-born individuals (Eschbach et al. 2007).

Low socioeconomic and legal position also hinders systematic, timely access to quality health care. Immigrants to the U.S. consistently report lower levels of health insurance coverage and less access to regular sources of care than other segments of the U.S. population (Derose et al. 2009; Singh and Hiatt 2006). Hispanics in particular report some of the lowest rates of coverage and the trend appears to have worsened in recent years (Rutledge and McLaughlin 2008). They lack private health insurance because they are typically employed in agricultural, manual labor, and other low-wage jobs which do not pay enough to purchase insurance. Also these jobs frequently do not offer employer-sponsored insurance or other benefits (Carrasquillo, Carrasquillo and Shea 2000). This is further exacerbated when immigrants also lack legal status (Chavez, Flores and Lopezgarza 1992) as access to publicly-funded options (Medicare for over age 65, Medicaid/SCHIP for low-income families and children) are also restricted by immigration status: only U.S. citizens and immigrants who have been legal permanent residents for at least 5 years are eligible for these benefits.

Public and private insurance are-important enabling factors of timely access to quality care. Yet as a result of difficulty accessing services, immigrants are less likely to report using health screening tests (Echeverria and Carrasquillo 2006). Lower access to health care and screening, in turn, can have serious health consequences if problems are detected late (or never) and by the severe limits to disease treatment faced by migrants related to their lack of access to health insurance (e.g. Pagán, Puig and Soldo 2007). Note, however, that even when insured and eligible for programs, migrants use fewer services and have lower medical expenses than US-born individuals (Ku 2009), indicating that they may still face other cultural or linguistic barriers to care (Pérez-Escamilla 2010). Although access and utilization of services improves over time spent in the U.S. (Akresh 2009; Angel, Angel and Markides 2002) and there is a patchwork of health services through which migrant workers may have access to basic screening (e.g. Diaz-Perez, Farley and Cabanis 2004), health care access is still very much a challenge and source of migrant vulnerability even when compared to the (less than ideal) health care access of people in sending communities in Mexico (Wong, Díaz and Higgins 2006).

Sources of Migrant Vulnerability in the Sending Country:

As mentioned above, the health status of return migrants, particularly older adults, seems to be slightly poorer than that of people (of similar levels of U.S. experience) remaining in the United States (Riosmena et al. Forthcoming-b; Turra and Elo 2008), which can be taken as an indication that their health status may have worsened throughout their time in the United States, or that many migrants may return due to sickness in old age. Either way, migration may not only exacerbate health vulnerability (through these negative acculturation changes), but also through migrants’lack of health insurance eligibility upon return. Although this situation has seemingly improved with the establishment of programs such as the Seguro Popular in Mexico and that, in theory, elderly return migrants are eligible to enroll, Riosmena et al. (2012) show that the coverage of Seguro Popular is lower for recent return migrants in places other than metropolitan areas, especially in rural areas.

Voluntary and forced return may also be creating new forms of vulnerability in transit and sending areas, in particular in recent years as the number of deportations has increased dramatically, averaging well more than a quarter million per year during the last decade and reaching almost 400,000 in 2009 (DHS 2011: Table 36). A recent study by Giorguli and Gutiérrez (Forthcoming) using the 2010 Mexican census finds an increase in return migration in the 2005-2009 period with a disproportionate number of return migrants located in northern border cities. These figures, along with journalistic reports, suggest that many deported migrants originally from the Mexican interior are staying in border cities (and migrant shelters in particular)7 , potentially biding their time before eventually re-attempting to cross, or to remain closer to their relatives still living in the United States (particularly, those with legal documents living in border states and who may be able to visit the deportee on the Mexican side). Whether or not this brings additional health challenges for these folks per se, their situation is certainly unstable and vulnerable, for instance, when encountering local police.

More clearly, the large number of deportations of both undocumented and otherwise legal migrants (found to be guilty of aggravated felonies) have certainly represented very pressing health challenges in some sending areas. Undocumented and legal immigrant youths from several Latin American countries (particularly, El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala), many with prior or current gang membership in the United States (especially to the MS-13 and M-18 gangs in the Los Angeles area), oftentimes find themselves not only deported to a country they barely know or remember, but to neighborhoods dominated by people belonging to rival gangs as deportation remaps the relatively well-ordered gang geography of their cities of former residence in perverse ways, increasing the death toll (De Cesare 2003; Ribando 2005) and incarceration of a nontrivial share of these youths (Zilberg 2004).8 As a consequence of this remapping, the few opportunities available for at-risk youth, their schooling/trade deficiencies, and the inflexible and inadequate response of local and national governments (Hagendorn 2008), migration has exacerbated certain kinds of social vulnerability in countries of origin, particularly among those unfortunate to end up in enemy territory by an accident of geography.

As mentioned in the outset, international migration may be an initial response to certain types of economic or social vulnerability among groups and individuals. The lack of access to services, potentially including health, and social security at large may be an additional motivation for people to go to the United States (Sana and Massey 2000). The confluence of a relative’s poor health status and lack of access to services could further be motivating other family members to migrate (though this is not one of the main reasons for migration). Additionally, the types of market failure associated with emigration according to the New Economics of Labor Migration perspective (Massey et al. 1993) could be precisely understood as responses to certain forms of vulnerability (e.g., lack of access to appropriate crop insurance). Likewise, the typical dislocation of local livelihoods associated with economic development processes (e.g., capital penetration, increased efficiencies in production, etc.) associated with Historical-Structural and World Systems Theories (Massey et al. 1993) may also suggest migration is due to increased vulnerability of different sorts.

Migration and the Health-related

Vulnerability of the Left Behind

Translocal ties originating from international migration processes transform sending areas in profound ways (e.g., Levitt 1998). Health is no exception, and the effects of migration seem to be both positive and negative not only for return migrants (as discussed above) but for nonmigrants as well. Circular migration following vulnerability in the U.S. is a vehicle of STD transmission (particularly HIV) into migrantsending communities (Bronfman, Sejenovich and Uribe 1998). The stress associated with the migration of relatives seems to take a toll in those left behind, who have to assume more responsibilities during the migrant’s absence, including becoming the primary breadwinner of the household for at least some time (e.g., Aysa and Massey 2004). This stress may take a toll in terms of depressive symptoms (Salgado de Snyder 1994).

Yet, the goal of migration is to improve the lives of those left behind, and it does in some ways. Several studies have demonstrated that remittance receipt and/or migration experience at the household and community scales are significantly associated with lower odds of low birth weight and infant mortality in Mexico (Frank 2005; Frank and Hummer 2002; Hamilton, Villarreal and Hummer 2009; Hildebrandt et al. 2005; Kana’iaupuni and Donato 1999; McKenzie 2006). However, these findings seem to be a result of the fact that these translocal exchanges (remittances, in particular) are accelerating the nutrition transition in sending areas. The nutrition transition refers to an increased availability of high fatty and processed foods and altered home cooking practices (Popkin 2001). While these changes translate into significant weight gains (beneficial for children in this context), they may eventually also imply unfavorable weight gains in more recent times, as suggested by studies finding that migration-related processes are associated with higher child/adolescent (Creighton et al. 2011) and adult obesity (Riosmena et al. Forthcoming- a) among the left behind in sending areas. As such, migration may be having other roles and unintended collateral consequences migrant communities and policymakers need to be aware of.

Conclusions

We have provided a brief overview of potential health-related vulnerability and resistance throughout various phases of the migration process. Many studies have shown that migrants are indeed vulnerable subjects in various dimension and that this vulnerability may have serious health consequences. In our view, the main sources of migrant vulnerability are legal and socioeconomic status, which hinder systematic, timely access to quality health insurance and health care. Upon return to their places of origin, migrants also face several barriers to access good health care, some related to their migrant status, and some also possibly motivating their emigration in the first place. Moreover, although migration reduces the (health) vulnerability of people in sending communities in various ways, it can also exacerbate it in others.

We have also shown that the health status of migrants is not always problematic or inferior to that, for instance, of people with better legal and socioeconomic standing in the United States. This may be evidence of migrant resiliency to existing vulnerability, both originating in the sending area (and by the selectivity of migration) and, potentially, in the destination area thanks to the strength of migrant networks in providing shelter and protection for migrants. The large variation in the health status of migrants (and nonmigrants), along with the types of data and statistical artifacts that these indicators are subject to, before, during, and after the migration process summarized here should be taken into consideration when designing studies of migrant health.

While the diagnosis provided here is not completely pessimistic, we have also shown a large body of evidence indicating that this resiliency indeed seems to wear out during the process of adapting to the United States. In our view, this is most likely the result of the accumulation of different types of disadvantage generally related to the low socioeconomic position and lack of legal status of migrants, which disproportionately expose them to health hazards and makes them oftentimes ineligible to be covered by the social safety net.

This has implications for immigration, health, and social development policy in sending countries and the United States. In sending countries, short of providing better economic opportunities for individuals (especially in the formal economy, which covers a more complete array of health services), public spending on health for the uninsured should help prevent the aforementioned health problems associated with the migration process. Despite the lower coverage of (older) return migrant adults (Riosmena et al. 2012), the establishment and expansion of the Seguro Popular in Mexico in 2007 is a step in the right direction. However, inter-state portability is still a challenge, which may affect migrants in transit to the United States, not to mention non- Mexican migrants doing the trek north.9 Although there have been recent efforts to expedite the affiliation process of migrants abroad by allowing them to register for this type of insurance in Consulates,10 this only covers them upon their return to Mexican territory. Yet, this coverage does not start in the sending community but can (in theory) take place in the border region, where migrants can also obtain certain forms of services covered by Seguro Popular while deciding if they will stay at the border, go to their communities of origin, or back to the U.S.11

This is one of the many efforts of the Mexican government to reach out to the migrant community. In terms of health, there are two main efforts involving several agencies and spearheaded by the Instituto de los Mexicanos en el Exterior. First, the Binational Health Week (taking place every October since 2001) has been an attempt to promote awareness on health issues affecting migrants by bringing together policymakers with community health workers and academics. Second, the Ventanillas de Salud are posts manned by local NGOs to raise health awareness among the immigrant community visiting the different Mexican consulates (Laglagaron 2010). Yet, again, the services provided in the Ventanillas are still pretty basic and provided by local NGOs of the sort previously described. As such, these initiatives are only but a good start to a much larger issue.

In the United States, as mentioned above, lack of longstanding permanent residence can severely hinder the ability of many migrants to receive health care, especially of those who may be in most dire need of it given their low socioeconomic position (also a partial result of their legal status). While it would be of course ideal that all migrants had access to Medicaid and to health insurance through the health exchanges that will be established as part of the most recent health reform overhaul, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) of 2010, which explicitly excluded the 11 million undocumented migrants in the country, 85% of whom hail from Latin America (Passel and Cohn 2009).

Legal migrants may also have access problems, especially if they decide to return to their country of origin after a life of work in the United States. Although social security checks can be received and cashed abroad, Medicare access is not portable for return migrants or U.S.-born retirees living overseas (Warner 2011). Clearly, making Medicare portable would provide an initial solution to the health problems and insufficient coverage of a population with rights of access to more comprehensive, better quality health services.

In sum, both the U.S. and sending country governments should seek to provide expanded health services to the populations they respectively (may) have a legal mandate to serve whether or not they are inside their territory. Currently, to the best of our knowledge, the only Binational public health insurance program available from either side is one offered by Mexican authorities to cover legal migrants with work contracts shorter than six months. Yet, barring any unlikely advance in comprehensive immigration reform or any amendments to the ACA in the United States, the more realistic solution then seems to continue finding mixed programs in which most levels of attention are given in the United States while catastrophic events could be covered in the sending country (see also Pardinas 2008: p. 25).

![]()

References

Abraído-Lanza, A.F., A.N. Armbrister, K.R. Flórez, and A.N. Aguirre. 2006. “Toward a Theory-Driven Model of Acculturation in Public Health Research.” American Journal of Public Health 96(8):1342-1346.

Abraído-Lanza, A.F., M.T. Chao, and K.R. Flórez. 2005. “Do healthy behaviors decline with greater acculturation? Implications for the Latino mortality paradox.” Social Science & Medicine 61(6):1243-1255.

Abraido-Lanza, A.F., B.P. Dohrenwend, D.S. Ng-Mak, and J.B. Turner. 1999. “The Latino mortality paradox: A test of the “salmon bias” and healthy migrant hypotheses.” American Journal of Public Health 89(10):1543-1548.

Adger, W.N. 2006. “Vulnerability.” Global Environmental Change 16(3):268-281.

Adler, N.E. and J.M. Ostrove. 1999. “Socioeconomic status and health: What we know and what we don’t.” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 896:3-15.

Akresh, I.R. 2006. “Occupational mobility among legal immigrants to the United States.” International Migration Review 40(4):854-884.

_____. 2007. “Dietary assimilation and health among Hispanic immigrants to the United States.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 48(4):404-417.

_____. 2009. “Health service utilization among immigrants to the United States.” Population Research and Policy Review 28(6):795-815.

Alba, R. and V. Nee. 2003. Remaking the American mainstream: Assimilation and contemporary immigration. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Angel, R.J., J.L. Angel, C. Díaz Venegas, and C. Bonazzo. 2010. “Shorter stay, longer life: Age at migration and mortality among the older Mexican-origin population.” Journal of Aging and Health 22(7):914-931.

Angel, R.J., J.L. Angel, and K.S. Markides. 2002. “Stability and change in health insurance among older Mexican Americans: Longitudinal evidence from the Hispanic established populations for epidemiologic study of the elderly.” American Journal of Public Health 92(8):1264-1271.

Aysa, M. and D.S. Massey. 2004. “Wives Left Behind: The Labor Market Behavior of Women in Migrant Communities.” Pp. 131-144 in Crossing the Border: Research from the Mexican Migration Project, edited by J. Durand and D.S. Massey. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Bardsley, D. and G. Hugo. 2010. “Migration and climate change: examining thresholds of change to guide effective adaptation decision-making.” Population & Environment 32(2):238-262.

Barquera, S., R.A. Durazo-Arvizu, A. Luke, G. Cao, and R.S. Cooper. 2008. “Hypertension in Mexico and among Mexican Americans: Prevalence and treatment patterns.” Journal of Human Hypertension 22(9):617-626.

Beard, H.A., M. Al Ghatrif, R. Samper-Ternent, K. Gerst, and K.S. Markides. 2009. “Trends in Diabetes Prevalence and Diabetes-Related Complications in Older Mexican Americans From 1993-1994 to 2004-2005.” Diabetes Care 32(12):2212-2217.

Bronfman, M., G. Sejenovich, and P. Uribe. 1998. “Migración y SIDA en México y América Central: una revisión de la literatura.” Consejo Nacional para la Prevención y Control del VIH/SIDA.

Bustamante, J.A. 2011. “La vulnerabilidad extrema de los migrantes: Los casos de Estados Unidos y México.” Migraciones internacionales 6(1):97-118.

Cagney, K.A., C.R. Browning, and D.M. Wallace. 2007. “The Latino paradox in neighborhood context: The case of asthma and other respiratory conditions.” American Journal of Public Health 97(5):919-925.

Carrasquillo, O., A.I. Carrasquillo, and S. Shea. 2000. “Health insurance coverage of immigrants living in the United States: Differences by citizenship status and country of origin.” American Journal of Public Health 90(6):917-923.

Casillas, R. 2011. “The dark side of globalized migration: The rise and peak of criminal networks—The case of Central Americans in Mexico.” Globalizations 8(3):295-310.

Castillo, M.A. 2000. “Las políticas hacia la migración centroamericana en países de origen, de destino y de tránsito.” Papeles de Poblacion(24):133-157.

Chavez, L.R., E.T. Flores, and M. Lopezgarza. 1992. “Undocumented Latin American immigrants and U. S. health services: An approach to a political economy of utilization” Medical Anthropology Quarterly 6(1):6-26.

Colón-López, V., M.N. Haan, A.E. Aiello, and D. Ghosh. 2009. “The effect of age at migration on cardiovascular mortality among elderly Mexican immigrants.” Annals of Epidemiology 19(1):8-14.

Creighton, M.J., N. Goldman, G. Teruel, and L. Rubalcava. 2011. “Migrant networks and pathways to child obesity in Mexico.” Social Science & Medicine 72(5):685-693.

Crimmins, E.M., B.J. Soldo, J.K. Kim, and D.E. Alley. 2005. “Using anthropometric indicators for Mexicans in the United States and Mexico to understand the selection of migrants and the ´Hispanic paradox´”. Social Biology 52(3-4):164-177.

Cunningham, S.A., J.D. Ruben, and K.M.V. Narayan. 2008. “Health of foreignborn people in the United States: A review.” Health & Place 14(4):623-635.

Curran, S.R. and E. Rivero-Fuentes. 2003. “Engendering migrant networks: The case of Mexican migration.” Demography 40(2):289-307.

De Snyder, V.N.S., T.G. Vazquez, I.B. Chapela, and C.I. Xibile. 2007. “Social vulnerability, health and migration from Mexico-United States.” Salud Pública de México 49:E8-E10.

Derose, K.P., B.W. Bahney, N. Lurie, and J.J. Escarce. 2009. “Review: Immigrants and health care access, quality, and cost.” Medical Care Research and Review 66(4):355-408.

Derose, K.P., J.J. Escarce, and N. Lurie. 2007. “Immigrants and health care: Sources of vulnerability.” Health Affairs 26(5):1258-1268.

Diaz-Perez, M.d.J., T. Farley, and C.M. Cabanis. 2004. “A program to improve access to health care among Mexican immigrants in rural Colorado.” Journal of Rural Health 20(3):258-264.

Donato, K.M., M. Stainback, and C.L. Bankston, III. 2005. “The economic incorporation of Mexican immigrants in southern Louisiana: A tale of two cities.” Pp. 76-100 in New destinations: Mexican immigration in the United States, edited by V. Zúñiga and R. Hernández-León. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Echeverria, S.E. and O. Carrasquillo. 2006. “The Roles of Citizenship Status, Acculturation, and Health Insurance in Breast and Cervical Cancer Screening Among Immigrant Women.” Medical Care 44(8):788-792 710.1097/1001.mlr.0000215863.0000224214.0000215841.

Eschbach, K., S. Al Snih, K.S. Markides, and J.S. Goodwin. 2007. “Disability and Active Life Expectancy of Older U.S.- and Foreign-Born Mexican Americans.” Pp. 40-49 in The health of aging Hispanics: The Mexican-origin population edited by J.L. Angel and K.E. Whitfield. New York: Springer.

Eschbach, K., J. Hagan, N. Rodriguez, R. Hernandez-Leon, and S. Bailey. 1999. “Death at the border.” International Migration Review 33(2):430-454.

Eschbach, K., Y.-F. Kuo, and J.S. Goodwin. 2006. “Ascertainment of Hispanic ethnicity on California death certificates: Implications for the explanation of the Hispanic mortality advantage.” American Journal of Public Health 96(12):2209-2215.

Eschbach, K., J.D. Mahnken, and J.S. Goodwin. 2005. “Neighborhood composition and incidence of cancer among Hispanics in the United States.” Cancer 103(5):1036-1044.

Eschbach, K., G.V. Ostir, K.V. Patel, K.S. Markides, and J.S. Goodwin. 2004. “Neighborhood context and mortality among older Mexican Americans: Is there a barrio advantage?” American Journal of Public Health 94(10):1807-1812.

Feliciano, C. 2005. “Educational selectivity in U.S. immigration: How do immigrants compare to those left behind?” Demography 42(1):131-152.

Frank, R. 2005. “International migration and infant health in Mexico.” Journal of immigrant health 7(1):11-22.

Frank, R. and R.A. Hummer. 2002. “The other side of the paradox: The risk of low birth weight among infants of migrant and nonmigrant households within Mexico.” International Migration Review 36(3):746-765.

GAO. 2006. “Illegal immigration: Border-crossing deaths have doubled since 1995; border patrol efforts to prevent deaths have not been fully evaluated.” Washington, D.C.: United States Government Accountability Office.

González, H.M., M.N. Haan, and L. Hinton. 2001. “Acculturation and the Prevalence of Depression in Older Mexican Americans: Baseline Results of the Sacramento Area Latino Study on Aging.” Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 49(7):948-953.

Gorman, B.K. and J.N.G. Read. 2006. “Gender Disparities in Adult Health: An Examination of Three Measures of Morbidity.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 47(2):95-110.

Griffith, D.C. 2005. “Rural industry and Mexican immigration and settlement in North Carolina.” Pp. 50-75 in New destinations: Mexican immigration in the United States, edited by V. Zúñiga and R. Hernández-León. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Hall, M., E. Greenman, and G. Farkas. 2010. “Legal Status and Wage Disparities for Mexican Immigrants.” Social Forces 89(2):491-513.

Hamilton, E.R., A. Villarreal, and R.A. Hummer. 2009. “Mother’s, household, and community U.S. migration experience and infant mortality in rural and urban Mexico.” Population Research and Policy Review 28(2):123-142.

Hanson, G.H. 2009. “The Economic Consequences of the International Migration of Labor.” Annual Review of Economics 1:179-207.

Hildebrandt, N., D.J. McKenzie, G. Esquivel, and E. Schargrodsky. 2005. “The Effects of Migration on Child Health in Mexico [with Comments].” Economia 6(1):257-289.

Hummer, R.A., D.A. Powers, S.G. Pullum, G.L. Gossman, and W.P. Frisbie. 2007. “Paradox found (again): Infant mortality among the Mexican-origin population in the United States.” Demography 44(3):441-457.

Jiménez, T.R. 2011. “Immigrants in the United States: How well are they integrating into society?”. Washington, D.C.: Migration Policy Institute. bit.ly/4bZXm5c. Last accessed January 30, 2012.

Johnson, J. 2008. “The forgotten border: Migration & human rights at Mexico’s southern border.” Latin America Working Group Education Fund.bit.ly/3LAyRkD.

Kana’iaupuni, S.M. and K.M. Donato. 1999. “Migradollars and mortality: The effects of migration on infant survival in Mexico.” Demography 36(3):339-353.

Kirschenbaum, A., L. Oigenblick, and A.I. Goldberg. 2000. “Well being, work environment and work accidents.” Social Science & Medicine 50(5):631-639.

Ku, L. 2009. “Health insurance coverage and medical expenditures of immigrants and native-born citizens in the United States.” American Journal of Public Health 99(7):1322-1328.

Laglagaron, L. 2010. “Protection through integration: The Mexican government’s efforts to aid migrants in the United States.” Washington, D.C.: Migration Policy Institute.

Landale, N.S., R.S. Oropesa, and B.K. Gorman. 2000. “Migration and infant death: Assimilation or selective migration among Puerto Ricans?” American Sociological Review 65(6):888-909.

Lara, M., C. Gamboa, M.I. Kahramanian, L.S. Morales, and D.E.H. Bautista. 2005. “Acculturation and latino health in the United States: A review of the literature and its sociopolitical context.” Annual Review of Public Health 26:367-397.

Lee, M.-A. and K.F. Ferraro. 2007. “Neighborhood residential segregation and physical health among Hispanic Americans: Good, bad, or benign?” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 48(2):131-148.

Levitt, P. 1998. “Social remittances: Migration driven local-level forms of cultural diffusion.” International Migration Review 32(4):926-948.

Lindstrom, D.P. 1996. “Economic opportunity in Mexico and return migration from the United States.” Demography 33(3):357-374.

Lopez-Gonzalez, L., V.C. Aravena, and R.A. Hummer. 2005. “Immigrant acculturation, gender and health behavior: A research note.” Social Forces 84(1):581-593.

Markides, K. and K. Gerst. 2011. “Immigration, aging, and health in the United States.” in Handbook of the sociology of aging, edited by J.L. Angel and R.A. Settersten, Jr. New York: Springer.

Markides, K.S. and K. Eschbach. 2005. “Aging, migration, and mortality: Current status of research on the Hispanic paradox.” Journals of Gerontology: Series B 60(Sp. Iss. 2 ):S68-S75.

_____. 2011. “Hispanic paradox in adult mortality in the United States.” Pp. 225-238 in International handbook of adult mortality, edited by R.G. Rogers and E.M. Crimmins. New York: Springer Publishers.

Markides, K.S., K. Eschbach, L.A. Ray, and M.K. Peek. 2007. “Census disability rates among older people by race/ethnicity and type of Hispanic origin.” Pp. 26-39 in The health of aging Hispanics: The Mexican-origin population edited by J.L. Angel and K.E. Whitfield. New York: Springer.

Martínez-Donate, A.P., M.G. Rangel, M.F. Hovell, J. Santibáñez, C.L. Sipan, and J.A. Izazola. 2005. “HIV infection in mobile populations: The case of Mexican migrants to the United States.” Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública 17(1):26-29.

Massey, D.S., J. Arango, G. Hugo, A. Kouaouci, A. Pellegrino, and J.E. Taylor. 1993. “Theories of international migration: A review and appraisal.” Population and Development Review 19(3):431-466.

Massey, D.S. and K.E. Espinosa. 1997. “What’s driving Mexico-U.S. migration? A theoretical, empirical, and policy analysis.” American Journal of Sociology 102(4):939-999.

Massey, D.S. and F. Riosmena. 2010. “Undocumented migration from Latin America in an era of rising U.S. enforcement.” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 630(1):294-321.

McKenzie, D.J. 2006. “Beyond Remittances: The Effects of Migration on Mexican Households.” Pp. 123-147 in International Migration, Remittances and the Brain Drain, edited by M. Schiff and C. Özden. Washington, D.C.: World Bank.

Menjivar, C. 2006. “Liminal legality: Salvadoran and Guatemalan immigrants’ lives in the United States.” American Journal of Sociology 111(4):999-1037.

Menjívar, C. 2000. Fragmented ties: Salvadoran immigrant networks in America. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Mikolajczyk, R., M. Bredehorst, N. Khelaifat, C. Maier, and A. Maxwell. 2007. “Correlates of depressive symptoms among Latino and Non-Latino White adolescents: Findings from the 2003 California Health Interview Survey.” BMC Public Health 7(1):21.

Mukhopadhyay, S. and D. Oxborrow. 2012. “The Value of an Employment-Based Green Card.” Demography 49(1):219-237.

Mulvaney-Day, N.E., M. Alegría, and W. Sribney. 2007. “Social cohesion, social support, and health among Latinos in the United States.” Social Science & Medicine 64(2):477-495.

Munshi, K. 2003. “Networks in the modern economy: Mexican migrants in the US labor market.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 118(2):549-599.

Myers, D., X. Gao, and A. Emeka. 2009. “The Gradient of Immigrant Age-at-Arrival Effects on Socioeconomic Outcomes in the U.S.1.” International Migration Review 43(1):205-229.

Nazario, S. 2006. Enrique’s journey. New York: Random House.

Orrenius, P. and M. Zavodny. 2009. “Do immigrants work in riskier jobs?” Demography 46(3):535-551.

Ostir, G.V., K. Eschbach, K.S. Markides, and J.S. Goodwin. 2003. “Neighborhood composition and depressive symptoms among older Mexican Americans.” Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 57(12):987-992.

Pagán, J.A., A. Puig, and B.J. Soldo. 2007. “Health insurance coverage and the use of preventive services by Mexican adults.” Health Economics 16(12):1359-1369.

Palloni, A. and E. Arias. 2004. “Paradox lost: Explaining the Hispanic adult mortality advantage.” Demography 41(3):385-415.

Palloni, A., M. McEniry, R. Wong, and M. Peláez. 2006. ” The tide to come: Elderly health in Latin America and the Caribbean.” Journal of Aging and Health 18(2):180-206.

Palloni, A. and J.D. Morenoff. 2001. “Interpreting the paradoxical in the Hispanic paradox: Demographic and epidemiologic approaches.” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 954:140-174.

Pardinas, J.E. 2008. “Los retos de la migración en México: Un espejo de dos caras.” Naciones Unidas, CEPAL.

Parrado, E.A., C.A. Flippen, and C. McQuiston. 2004. “Use of Commercial Sex Workers among Hispanic Migrants in North Carolina: Implications for the Spread of HIV.” Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health 36(4):150-156.

Passel, J.S. and D.V. Cohn. 2009. “A Portrait of Unauthorized Immigrants in the United States.” edited by P.H. Center. Washington, D.C.: Pew Hispanic Center.

Passel, J.S., D.V. Cohn, and A. Gonzalez-Barrera. 2012. “Net Migration from Mexico Falls to Zero–and Perhaps Less.” edited by P.H. Center. Washington, D.C.: Pew Hispanic Center.

Patel, K.V., K. Eschbach, L.A. Ray, and K.S. Markides. 2004. “Evaluation of mortality data for older Mexican Americans: Implications for the Hispanic paradox.” American Journal of Epidemiology 159(7):707-715.

Patel, K.V., K. Eschbach, L.L. Rudkin, M.K. Peek, and K.S. Markides. 2003. “Neighborhood context and self-rated health in older Mexican Americans.” Annals of Epidemiology 13(9):620-628.

Pérez-Escamilla, R. 2010. “Health care access among Latinos: Implications for social and health care reforms.” Journal of Hispanic Higher Education 9(1):43-60.

Popkin, B.M. 2001. “Nutrition in transition: The changing global nutrition challenge.” Asia Pacific Journal of Clinical Nutrition 10(Suppl.):S13-S18.

Riosmena, F., B. Everett, R.G. Rogers, and J.A. Dennis. 2011. “Paradox lost (over time)? Duration of stay and adult mortality among major Hispanic immigrant groups in the United States.” in Paper presented at the 2011 Population Association of America Meetings. Washington, D.C.

Riosmena, F., R. Frank, I.R. Akresh, and R. Kroeger. Forthcoming-a. “U.S. Migration, Translocality, and the Acceleration of the Nutrition Transition in Mexico.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers.

Riosmena, F., C. González-González, and R. Wong. 2012. “El retorno de los adultos mayores de Estados Unidos: salud, bienestar y vulnerabilidad.” Coyuntura Demográfica(2).

Riosmena, F., A. Palloni, and R. Wong. Forthcoming-b. “Migration selection, protection, and acculturation in health: A bi-national perspective on older adults.” Demography.

Rubalcava, L.N., G.M. Teruel, D. Thomas, and N. Goldman. 2008. “The healthy migrant effect: New findings from the Mexican family life survey.” American Journal of Public Health 98(1):78-84.

Rumbaut, R.G. 1997. “Paradoxes (and orthodoxies) of assimilation.” Sociological Perspectives 40(3):483-511.

Rutledge, M.S. and C.G. McLaughlin. 2008. “Hispanics and Health Insurance Coverage: The Rising Disparity.” Medical Care 46(10):1086-1092 1010.1097/MLR.1080b1013e31818828e31818823.

Salgado de Snyder, V.N. 1994. “Mexican women, mental health and migration: those who go and those who stay behind.” Theoretical and conceptual issues in Hispanic mental health:114-139.

Salgado de Snyder, V.N., T. González Vazquez, I. Bojorquez Chapela, and C. Infante Xibile. 2007. “Vulnerabilidad social, salud y migración México-Estados Unidos.” Salud Pública de México 49(sp.):8-10.

Sana, M. and D.S. Massey. 2000. “Seeking social security: An alternative motivation for Mexico-US migration.” International Migration 38(5):3-24.

Singh, G.K. and R.A. Hiatt. 2006. “Trends and disparities in socioeconomic and behavioural characteristics, life expectancy, and cause-specific mortality of native-born and foreign-born populations in the United States, 1979-2003.” International Journal of Epidemiology 35(4):903-919.

Singh, G.K. and B.A. Miller. 2004. “Health, life expectancy, and mortality patterns among immigrant populations in the United States.” Canadian Journal of Public Health 95(3):I14-I21.

Singh, G.K. and M. Siahpush. 2002. “Ethnic-immigrant differentials in health behaviors, morbidity, and cause-specific mortality in the United States: An analysis of two national data bases.” Human Biology 74(1):83-109.

Spener, D. 2009. Clandestine crossings: Migrants and coyotes on the Texas- Mexico border. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Teitler, J.O., N. Hutto, and N.E. Reichman. 2012. “Birthweight of children of immigrants by maternal duration of residence in the United States.” Social Science Medicine 75(3):459-468.

Téllez, M.E.A. and A.P.T. Peña. 2007. “Vigilance and control at the U.S.-Mexico border region. The new routes of the international migration flows. ” Papeles de Poblacion 13(51):45-75.

Turra, C.M. and I.T. Elo. 2008. “The impact of salmon bias on the Hispanic mortality advantage: New evidence from social security data.” Population Research and Policy Review 27(5):515-530.

Warner, D.C. 2011. “Access to health services for immigrants in the USA: from the Great Society to the 2010 Health Reform Act and after.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 35(1):40-55.

Wong, R., J.J. Díaz, and M. Higgins. 2006. “Health Care Use Among Elderly Mexicans in the United States and Mexico.” Research on Aging 28(3):393- 408.

Zilberg, E. 2004. “Fools banished from the kingdom: Remapping geographies of gang violence between the Americas (Los Angeles and San Salvador).” American Quarterly 56(3):759-779.

![]()

1 See cnn.it/3WzQl6G. Last accessed February 14, 2012.

2 For instance, Orrenius and Zavodny (2009: Table 1) find a higher share of immigrants in industries and occupations with higher fatality rates.

3 However, note that the association between acculturation and health is not uniformly negative. For example, it is positively associated with exercise and other measures of leisure time physical activity among foreign-born persons (Abraído-Lanza et al. 2005). Similarly, Latinos with higher acculturation scores have a lower likelihood of exhibiting depressive symptoms than their counterparts with lower scores (González, Haan and Hinton 2001; Mikolajczyk et al. 2007).

4 While the lack of legal immigration pathways under the auspices of political, family, or job-related provisions of U.S. immigration law may deter some individuals from emigrating, many still cross without documents responding to incentives in both sending and destination areas (Massey and Riosmena 2010). Although it is beyond the scope of this paper to discuss the reasons why people migrate without documents, suffice to say “push” factors in sending countries are not the only factors that explain why people venture into the dangers and stress of crossing and living without documents: labor demand has a very important role as well (Hanson 2009).

5 The deferred action program recently announced by the Obama administration, aimed to allow young undocumented migrants who can prove they were brought to the U.S. by their parents to (temporarily) avoid deportation and be given temporary work/residence permission, may change this situation considerably. However, as of this writing, the program has not been implemented in any substantial way that would allow us to fully consider its potential benefits.

6 Undocumented immigrants are indeed entitled to many work protections, but they have no clear way to enforce them in the legal system without risking getting caught by immigration authorities, so many do not come forward when employers abuse them or provide them with subpar working conditions.

7 For instance, see bit.ly/4fjQwKG. Last accessed July 9, 2012.

8 See also bit.ly/4cWnj72. Last accessed July 9, 2012.

9 Even if portability issues were fixed, this insurance would of course otherwise only cover Mexican nationals or legal residents of Mexico with prior affiliation to this form of insurance.

10 bit.ly/3LXExW5. Last accessed July 8, 2012.

11 bit.ly/3LCawL3 Last accessed February 14, 2012.