Dual citizenship trends and their implication for the collection of migration statistics

Edición: Vol.6 Núm.2 mayo-agosto 2015

|

This paper examines globalization’s effect on the collection of international migration statistics, specifically related to an associated rise in dual citizenship. While dual citizenship has grown in recent decades, there has been little empirical research to measure its size, characteristics, or the impact dual nationals have had on migration data systems. Potential reasons for growth and data on both size and characteristics of dual citizens from recent censuses in the UNECE region are examined, in an attempt to ascertain their impact on migration statistics, particularly the use of data from countries of destination to estimate emigration from origin countries. While much more data are needed, results show that while still a small group in most countries, the number of dual citizens is rapidly increasing. The potential impact this could have on future migration statistics, as well as ways to improve data collection, analysis, quality, and dissemination, are discussed.

Key words: dual-citizenship, international migration statistics, globalization. |

El presente artículo analiza el efecto de la globalización en la recolección de estadísticas sobre migración internacional, específicamente las relacionadas con un aumento vinculado en la doble ciudadanía. Mientras que ésta ha aumentado en décadas recientes, ha habido poca investigación empírica para medir su dimensión, características o el impacto que las dobles nacionalidades han tenido en los sistemas de datos sobre migración. Analizamos algunas razones probables que expliquen el crecimiento y la información tanto en la dimensión como en las características de las dobles ciudadanías de censos recientes en la región de la Comisión Económica para Europa de las Naciones Unidas (UNECE, por sus siglas en inglés) en un intento por determinar su impacto en estadísticas de migración; sobre todo el uso de información de países de destino para calcular la migración desde los países de origen. Aunque se requiere de más información, los resultados muestran que aunque se trata de un grupo pequeño en la mayoría de los países, la cantidad de ciudadanos con doble nacionalidad va en aumento rápidamente. También se discute el impacto potencial que esto podría tener en las estadísticas futuras sobre migración, así como en ciertas formas de mejorar la recolección de información, el análisis, calidad y difusión.

Palabras clave: doble nacionalidad, estadísticas de migración internacional, globalización. |

Recibido: 18 de noviembre de 2014

Aceptado: 2 de marzo de 2015

I. Introduction

A by-product of world globalization has been increased movement of populations across international borders. As world economies are further integrated, in many regions visa-free labour agreements between countries encourage the “free” trade of goods and movement of people. Increased international migration results in the acquisition of new citizenships through naturalization, as well as bringing more people of different nationalities into contact with one another, resulting in inter-country marriages (or partnerships), and children from those relationships. Multiculturalism has increasingly been embraced by countries, particularly from an integration perspective. As such, the concept of a singular “nationality” or “citizenship” has become increasingly blurred, with many individuals possessing more than one citizenship. Is it possible that a rise in the number of “dual citizens” could have an implication on the way we traditionally collect migration data? Could these “dual nationals” impact measurement of emigration via the use of inter-country data exchange and mirror statistics?

Citizenship is thought to consist of four dimensions: legal status, rights, political membership, and sense of belonging (Bosniak 2000). There is a fair amount of recent literature on the concept of dual citizenship, though this is almost exclusively from a “policy” perspective, as opposed to statistical measurement. Some issues that are associated with dual citizens are related to voting rights, military service (and the general question of “loyalty”), its role to facilitate the integration process of immigrants, rights to social services, taxation, and even diaspora engagement. However, this paper is concerned with how and to what extent dual citizens are measured, and how this impacts the collection and measurement of migration statistics.

It is assumed that dual citizenship has grown in recent decades, as immigration increases and countries become more and more tolerant towards it, but there has been little empirical research to back this assertion. We know little about the size, characteristics, and impact of dual nationals. Even basic questions such as whether dual nationals are more mobile than other populations remain unanswered. However, as will be seen later, countries in the UNECE region have started to collect this information, though dissemination of data is less readily available.

II. Pathways toward Dual Citizenship

While there is no internationally recognized definition for dual citizenship, it is defined here as a person who concurrently holds legal citizenship status in more than one nation-state. While it is certainly possible (and increasingly likely) for a person to have more than two citizenships at the same time, this level of complexity is not addressed in this paper, as “dual” and “multiple” citizens are treated synonymously.

There are a number of different ways that a person can become a dual citizen, including both “active” and more “passive” means. An example of an “active” pathway would be naturalization of an immigrant in a country of residence, while still retaining citizenship of a previous country (though this often is not allowed by the country of naturalization or origin). This pathway is often facilitated/accelerated by marriage with a citizen of the country of naturalization. An example of a “passive” pathway towards dual citizenship is being born to parents of two different nationalities. This path is often allowed in countries that do not allow naturalized citizens to retain their original citizenship. Another “passive” case could be children of migrants born into their country of citizenship (e.g. Mexican parents in the United States, where the child automatically receives US citizenship by being born there, but is also eligible for their parents’ Mexican citizenship).

Ancestry is also a potential driver of dual citizenship. Descendants of migrants are often eligible to receive the citizenship of their forefathers, in which case at least one paternal grandparent or even great grandparent (e.g. Italy) is often sufficient to be eligible to claim citizenship status. For example, Germany granted German citizenship to 2.4 million descendants of “ethnic Germans” between 1990 and 2005, while Hungary, Romania, and Bulgaria have all recently introduced laws to facilitate the granting of citizenship to many people living in countries outside the EU (Mateos 2013). It must be noted that the pool of eligible dual citizens is far greater than the actual number of dual citizens. In the case of Italy, with liberal citizenship requirements, it is estimated that up to 60 million people could be eligible for Italian citizenship worldwide (Tintori 2009), which is about the same size as Italy’s current resident population.

III. Reasons for Growth

A number of reasons have been postulated for the presumed growth in dual citizenship in recent decades. These include large and circular migration flows, growing rates of naturalization, provisions for jus sanguinis (“right of blood”) in national legislation, children from increasing international marriages, and less direct reasons, like reduction in warfare between countries and demise of military conscription, as well as expansion of the international human rights regime (Kivisto and Faist 2007).

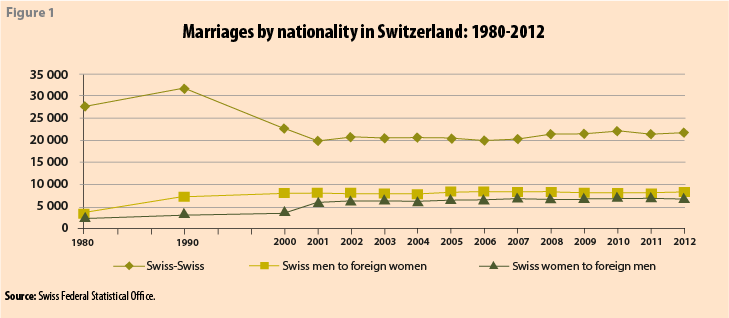

To take just one example of these drivers of growth, research has been conducted examining the rise of international marriages, for example in Asia (Jones and Chen 2008) and Europe (Lanzieri 2011). In summary, international marriages were found to have dramatically increased in countries like South Korea, Taiwan, Japan, and China, with similar patterns found in Europe, especially in Mediterranean countries like Italy and Spain. Figure 1 shows the extreme example of Switzerland, where nearly half of marriages are international. Increases in international marriages between Swiss and non-Swiss grew during the 1980s, particularly for Swiss men, though Swiss women had nearly closed the gap by 2001. Meanwhile, Swiss-to-Swiss marriages dramatically decreased from 1990 to 2001. The number of international and non-international marriages involving Swiss has remained relatively stable since that time.

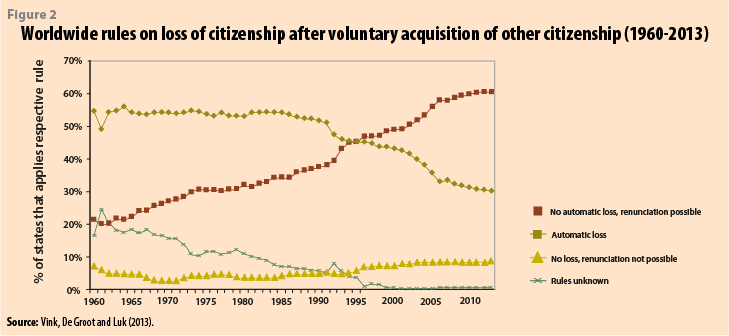

No matter the reasons, more countries now allow for dual citizenship than in the past, as can be seen in Figure 2. Since 1960, the number of countries for which citizenship is automatically lost after voluntary acquisition of another citizenship has dropped from about 60% to 30%. These trends are consistent with other studies and databases on national legislation related to dual citizenship (Faist et al. 2008, EUDO Observatory on Citizenship, UN World Population Policy Database).

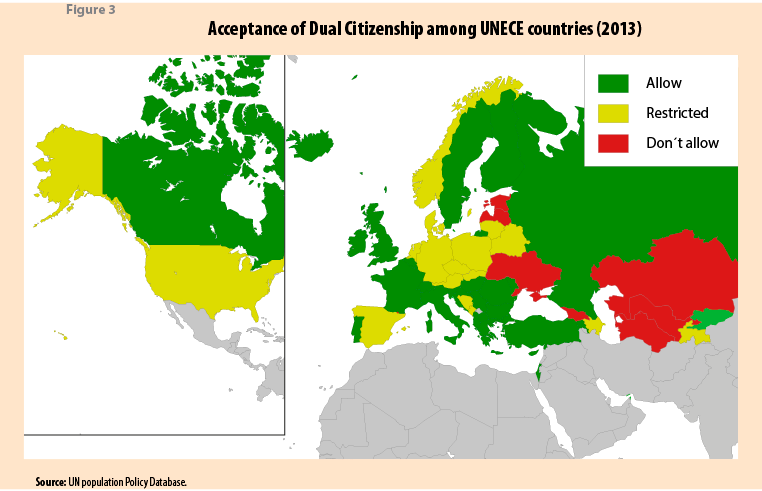

Based on most recent data, most countries in the UNECE region allow for dual citizenship, though many do so with restrictions. UNECE countries that do not allow dual citizenship under any circumstances tend to be located in Central Asia and parts of Eastern Europe and the Baltics.

Restrictions on dual citizenship are generally less restrictive for current citizens of countries, as opposed to those wishing to become citizens through the naturalization process. While laws differ among individual countries, restricted countries generally allow for dual citizenship for those who acquire dual citizenship at time of birth (two parents of different citizenship or born in a country that confers citizenship through birth —e.g. USA). However, many of these countries restrict dual citizenship upon naturalization, depending on the immigrant’s country of origin (e.g. upon naturalization in Germany one must renounce prior citizenship unless they are from an EU country or Switzerland).

IV. Impact of Dual Citizenship on Migration Statistics

To what extent could the rise of dual-citizenship impact our measurement of the migration phenomena? A potential issue arises when migration data (on either “stocks” or “flows”) are collected on the basis of country of citizenship, as opposed to country of birth. While collection of data by country of birth is preferable in some regards, due to its permanence (country of citizenship can change over time) and is a true measure of migration (foreigners can be born in their country of residence), it is not deemed to be as policy relevant as country of citizenship. Most migration flow data are still collected using country of citizenship as their measure for immigration. The greatest potential problem of dual citizenship, while using country of citizenship data to measure migration, emerges when “mirror” statistics are used as a strategy to estimate emigration from an origin country using immigration data from destination countries.

As has been well established, countries are much better able to measure those who enter than who leave a country (UN 1980). Thus, the international community has often encouraged data exchange to use destination country immigration data to help origin countries estimate their outmigration flows (e.g. 2009 UNECE Task Force on “Measuring Emigration Using Data Collected by the Receiving Country”).

However, when a dual citizen leaves (country of origin) or enters (country of destination) another country to which they are citizens, they are recorded as if they were citizens of those countries. For example, a Romanian/Moldovan citizen who moved from Moldova to Romania would be counted as a Romanian in-migrant to Romania with Romanian data sources, and as a Moldovan out-migrant from Moldova with Moldovan data. If this person moved again from Romania to another country in the EU, presumably on a Romanian passport, their subsequent moves would not be recorded as Moldovan citizens, but rather as Romanian. Thus, if there are a large number of dual Romanian/Moldovan citizens who migrate, and if Romanian data sources on immigration were used by Moldova to measure emigration of its citizens, then it is very likely that they would greatly underestimate the number of Moldovan emigrants to Romania (and to other countries in the EU).

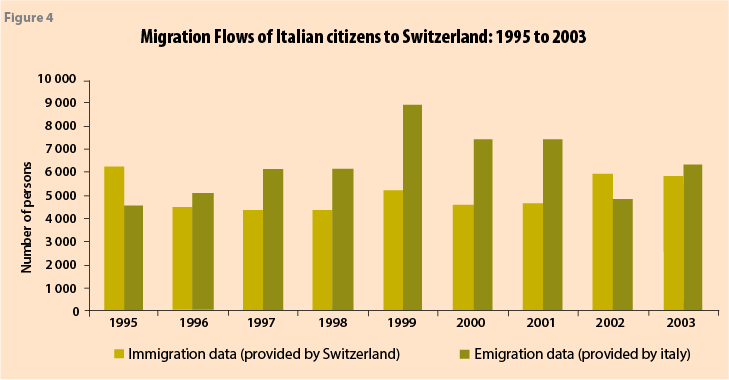

Taking another example, the UNECE Task Force on “Measuring Emigration Using Data Collected by the Receiving Country” included a data exchange exercise between countries, part of which can be seen in Figure 4. As a result of data exchange between Italy and Switzerland, Italian data on Italian citizens moving to Switzerland were found to be much higher than Swiss data on Italian immigration to Switzerland, by a magnitude of about 3,000 persons in 2000. As will be seen later, based on the 2000 Swiss Census, the largest stock of Swiss dual-citizens were Swiss-Italians (141,000). One possible explanation for this discrepancy could be the movement of Swiss-Italians, who are counted as Italian in Italian data sources on emigration, and Swiss in Swiss data sources on immigration.

It is interesting to note that the UNECE Task Force guidelines do not mention the issue of dual citizenship at any time during their recommendations. Perhaps this is due to the belief that the magnitude of dual-citizenship was not large enough to merit concern. What evidence is there on the size and growth of dual citizens in the UNECE region? Are they large enough to have an impact on the use of mirror statistics to estimate emigration, or could they have one in the immediate to long-term future? As shown above, at least in the case of Switzerland, they possibly do.

V. Magnitude of Dual Citizenship

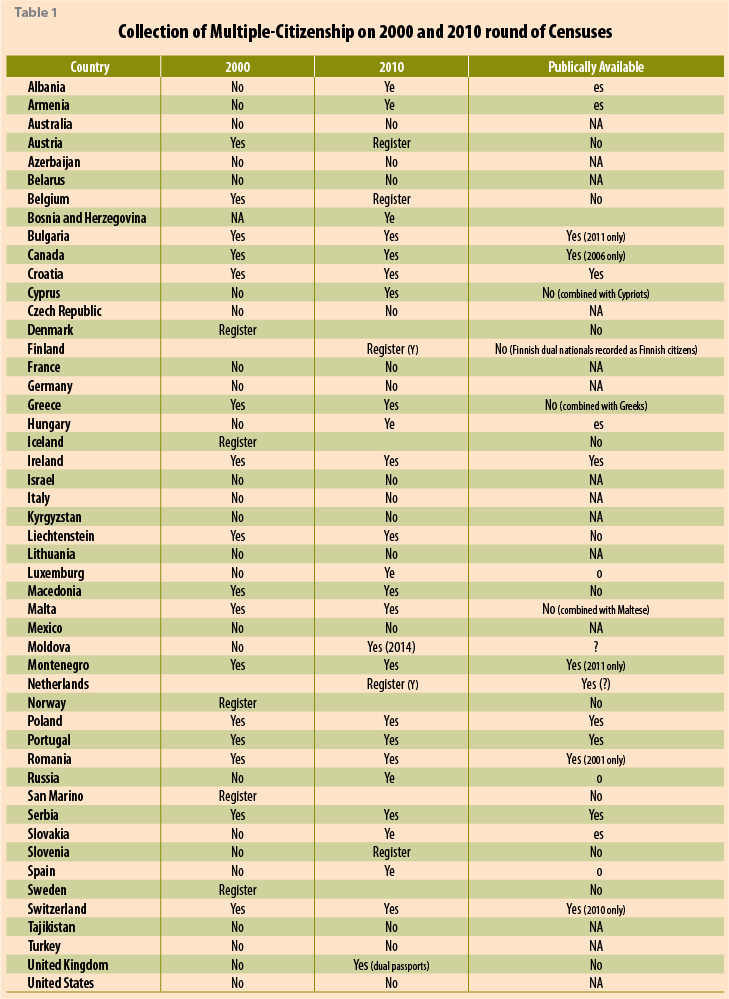

In general there is a dearth of information on the number of persons possessing dual-citizenship. Though the collection of multiple citizenship information is recommended on both the 2010 UN Principles and Recommendations for Population and Housing Censuses and the CES Recommendations for the 2010 Censuses of Population and Housing, as seen in Table 1, multiple citizenship information was not collected during the 2010 round of censuses in about half of the UNECE region, including large immigration receiving countries like France, Germany, Italy, and the United States. In addition, information on multiple citizenship is often not collected on population registers, and is in fact forbidden by law to be collected in some countries (e.g. the Netherlands as of January 2014). As far as other data sources are concerned, dual-citizenship information is sometimes available on national household surveys, such as labour force surveys, though not at the EU level. As can also be seen in Table 1, even when data are collected, they are often not publically available or information on dual nationals is combined with nationals (e.g. Cyprus, Greece, and Malta).

It is also unclear to what extent respondents accurately report dual-national status. From conversations with NSOs, some feel it is under-reported (e.g. Canada, that does not test the quality of this question on its census), while others think it is over-reported on household survey instruments (e.g. the Spanish LFS, which yields numbers higher than Census results, possibly due to sampling considerations). While it still needs investigation, I suspect, in general, it is likely dual citizenship is under-reported in data sources.

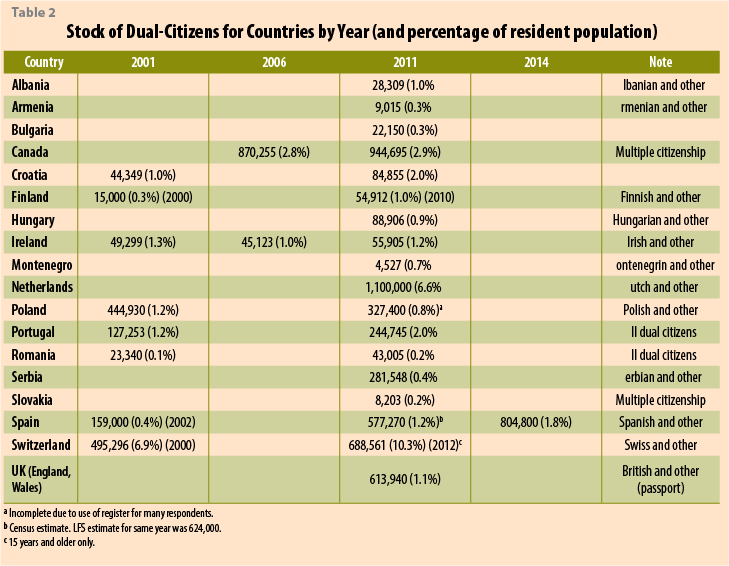

Table 2 compiles publically available (including some non-public special tabulations) information from UNECE countries on the stock of dual-nationals over time, primarily using censuses or other survey data.1 In some cases, countries only reported resident dual nationals from their own country, while others provided numbers for all resident dual nationals (see table notes). As it can be seen, the number of dual nationals varies greatly by country, though in general they make up only a small percentage of the total population. Numbers range from close to one million in the Netherlands (7% of the total population) and Canada (3% of the total population) to much smaller numbers in countries like Armenia, Bulgaria, Hungary, Montenegro, Romania, Slovakia, and Serbia (all less than 1% of the total population). The largest share of dual nationals (for countries for which data are available) are found in Switzerland, where about 10% (of those over 15 years of age) were dual nationals in 2012. Spain, Portugal and Croatia also have relatively higher percentages of dual nationals (about 2% of their total populations). One would expect to find more dual nationals in large immigration receiving countries, which is why lack of data for countries like the United States, France, Germany, Italy, and Australia limit the scope of this analysis.

However, one pattern is evident for countries that provide data over time. Though data are limited, the stock of dual citizens increased dramatically over the intercensal period, 100% or more for many countries. At the extreme, Spain experienced a dramatic increase in dual nationals from 2002 to 2014, with numbers increasing from 159,000 to 805,000. Similarly, according to dual nationality statistics in the Netherlands, the number of Dutch dual citizens tripled between 1995 and 2009 (Nicolaas 2009), as did Finnish dual citizens between 2000 and 2010. Croatia, Portugal, and Romania all doubled their number of dual citizens between 2000 and 2010. Even in a country like Ireland, which only had modest growth (20%) in dual citizens between 2006 and 2011, the percentage increase of Irish-European citizens was 89%, off-setting a loss of Irish-English citizens. This rapid growth in dual citizenship could have implications for future measurement of migration statistics.

VI. Characteristics of Dual Citizens

It would be interesting to examine the characteristics of dual-citizens, though most publically available data only provide counts, disaggregated by sex, age, and sometimes country of dual nationality. From what is available, patterns seem to differ based on different country contexts. Countries of dual nationality often tend to be from neighbouring countries, which is consistent with findings on migration in general (migrants tend to move shorter distances). For example, from a special tabulation of 2000 Swiss Census data, one sees that over half (56%) of all Swiss dual citizens were also Italian, French, or German. Similarly, for the most recent year for which data are available, 70% of Armenian dual nationals are Russian citizens, over ¾ of dual citizens in Poland are also German, about half of dual citizens in Albania are also Greek, and the largest number of dual citizens in Finland were Russian (28%). An exception to this geographic pattern is seen in Canada, where the largest number of dual citizens have UK citizenship, followed by the United States. Similarly related to its colonial past, in Spain the largest number of dual citizens came from the countries of Ecuador, Colombia, Argentina, and Peru (45% of all Spanish dual citizens). Finally, about half of Dutch dual citizens also have Turkish or Moroccan citizenship, likely reflecting recent immigration patterns.

Looking at the age and sex distribution of dual nationals, once again different patterns are found depending on specific countries. In Switzerland, based on 2000 data, dual-citizens were more likely to be female (60%) and tended to be younger than the general population (25% of dual citizens were under 15 years of age, compared to 17% of the general population). While Swiss data on dual citizens from 2010 are limited to those 15 years and older, the majority are still female (57%). While Spain did not have large differences between male and female dual citizens, dual citizens tended to be younger than the general population (36% under the age of 24 vs. 25% of the general population, and 72% under the age of 44 vs. 55% of the general population), which likely coincides with characteristics of international migrants to Spain.

In other countries, dual citizens were disproportionately likely to be of the working age population. While Montenegrin dual citizens were more likely to be female (57%), they were also more likely to be older than the general population (65% between the ages of 30 and 69 vs. 50% of the general population). Dual nationals in Portugal and Hungary were not different from the general population in terms of sex distribution, but both were more likely to be between the ages of 30-44 than the general population (30% vs. 23% in Hungary, and 32% vs. 22% in Portugal). Armenian dual nationals were more likely to be male (57%), while also more likely to be between the ages of 30-49 (37% vs. 26% of the general population).

As can be seen, different patterns in country of other citizenship, age, and sex are found in all countries, which suggest that growth of multi nationals is fuelled by different factors in different countries. For example, international-marriage in Switzerland and Spain, immigration from past colonies in Spain, return of labour migrants from Russia and ties to the former Soviet Union in Armenia, and naturalization of and births to recent immigrants to the Netherlands, could all be possible factors in the growth of dual citizenship in these countries.

It would also be interesting to investigate how dual nationals might differ from nationals in terms of other socio-economic characteristics, like education and employment. I suspect dual-nationals are more mobile than the general population, which would mean despite relatively low numbers, they could have a greater likelihood of impacting migration flow statistics, if they are more likely to make such moves.

Given lack of data on dual citizens in large immigrant receiving countries, it is difficult to determine the extent to which dual citizens hamper the use of immigration statistics from receiving countries to estimate emigration for sending countries. For countries for which data are available, in general, the stock of dual citizens is small, with the exception of Switzerland, where they currently make up 10% of the population. As such, it is likely that dual citizens do not greatly impact overall migration flow statistics at the moment. However, available data show that dual citizenship is a rapidly growing phenomenon in all countries (greater than 100% in some cases), though growth rates differ greatly. In the future, if dual-citizens are shown to be more mobile than the general population and current growth trends continue, combined with growing acceptance of dual citizenship in national legislation, this could likely impact the results of citizenship-based immigration data, particularly if these data are used to estimate emigration by other countries.

VII. Implications and Future Work

As described above, globalization has led to an increase in the number of people possessing dual citizenship, which could have an impact on the collection of migration statistics. While data are limited, the number of dual citizens remains relatively small, but is growing rapidly. This trend has the potential to impact estimates of emigration or diaspora populations using data sources from other countries (on the stock of emigrants/diaspora or immigration flows by country of citizenship). This could greatly impact high emigration countries which struggle to produce emigration estimates and need immigration statistics from countries of destination to produce these numbers. The growth of dual citizenship could also impact the use of mirror statistics, as currently promoted by Eurostat, to help evaluate emigration estimates produced by countries.

Even with this background, there is still a paucity of information collected by countries about dual citizens. While many countries now include this information on data collection instruments (e.g. Census or household surveys), many still do not, and even for those who do, data are often not publically released for this population group, who are either deemed too small or irrelevant for policy purposes (e.g. the country does not allow naturalized citizens to retain former citizenship, thus are not deemed important to measure). Obviously, a first step would be to include a measure of dual citizenship on data collection instruments. Questions could be easily added or modified to censuses or household surveys, though perhaps it would be more difficult to include these in register-based data systems.

Once data are collected, the next question is related to the accuracy of these data, and to what extent self-reported dual citizenship actually measures the phenomenon. Evaluation of these data, and to what degree they under- or over-represent the true number of dual citizens should be conducted. Given dual-nationality is a relatively rare event in many countries, it could also be difficult to accurately measure this group with household survey data due to sampling limitations.

Even among countries that collect information on dual citizenship, it is rare to see it included on publically released tables and datasets. The release of information on dual nationals in the EU is hampered by guidelines produced by Eurostat’s 2007 Task Force on Core Social Variables (revised in 2011). These guidelines recommend that on EU social surveys a person with two or more citizenships be allocated to only one country, based on the following preferences: reporting country, other EU member state (and if both are EU countries other than the reporting country, then it is the respondent’s choice or primary citizenship in the administrative record), and finally a country outside the EU. These guidelines apply to a number of social surveys in the EU, including the labour force survey, survey on income and living conditions, European Survey on Health and Social Integration, and even the census. Obviously, following these recommendations, which as previously shown are opposed to international census recommendations on the collection of dual citizenship data, would make the study of dual citizenship impossible in the EU.

Finally, data on dual citizens should be analysed at the country-level, to determine what characteristics dual citizens possess, to what extent they are highly mobile, and what countries they share nationalities with. These sorts of information could be used in models to help estimate the number of dual-citizens included in immigration streams, thereby improving the ability of using other country data to estimate emigration.

In summary, there is still much work to be done to evaluate the impact of the growing trend of dual citizenship, not only in terms of data collection, but also in terms of data quality assessment and analysis. While still relatively small in number, the number of dual citizens is likely to continue to grow, thus more likely to impact future migration measurement, in particular for citizenship-based immigration statistics. An alternative to “country of citizenship” is to use “country of birth” as the basis for measuring migrants, but this does not have the same policy relevance as citizenship information. While this paper primarily addresses the issue of using immigration-flow data to measure emigrant flows, other research on dual citizenship could also be conducted, not only to determine its size and characteristics, but also the impact dual citizenship has on maintaining ties to countries of origin (e.g. diaspora), sending remittances, or even social integration issues (e.g. whether it encourages naturalization or not). What we know about dual citizens is limited, and a first step would be improving the evidence base, followed by more detailed analysis of this growing group of persons.

![]()

References

Bosniak, L. (2000). “Citizenship denationalized”. Ind. J. Global Legal Studies. 7, 447-509.

EUDO Observatory on Citizenship, European University Institute. Country Profiles. DE (18/11/14, http://eudo-citizenship.eu/country-profiles).

Eurostat (2011). Implementing core variables in EU social surveys: Methodological guidelines. Luxembourg.

Faist, T. and J. Gerders (2008). “Dual Citizenship in an Age of Mobility”. Migration Policy Institute, Washington D.C.

Jones, G. and H. Shen (2008). “International marriage in East and Southeast Asia: trends and research emphases”. Citizenship Studies Vol. 12, No. 1, February 2008.

Lanzieri, G. (2011). “A Comparison of Recent Trends of International. Marriages and Divorces in European Countries”. IUSSP working paper prepared for the seminar on Global Perspectives on Marriages and International Migration, South Korea, October 2011.

Kivisto, P., & T. Faist (2007). Citizenship: Discourse, Theory and Transnational Prospects. Oxford: Blackwell.

Mateos, P. (2013). “External and Multiple Citizenship in the European Union. Are ‘Extracitizenship’ practices challenging Migrants Integration Policies?”. Paper presented at 2013 Population Association of America Meeting, New Orleans, USA.

Nicolaas, H. (2009). “Just over 1.1 million Dutch people have more than one nationality”. Web magazine, 15 December, 2009. CBS of Netherlands.

Tintori, G. (2009). “Fardelli d’Italia? Conseguenze nazionali e transnazionali delle politiche di cittadinanza italiane”. Carocci: Rome.

Vink, M., G. R. de Groot and C. Luk (2013). MACIMIDE Global Dual Citizenship Database. Version 1.02. Maastricht: Maastricht University.

United Nations (1980). Recommendations on Statistics of International Migration. Statistical Papers, No. 58. Sales No. E.79.XVII.18. New York.

_______ (2008). Principals and Recommendations for Population and Housing Censuses. New York.

_______ (2013). The World Population Policies Database. Department of Economic and Social Affairs. New York. DE (18/11/14, http://esa.un.org/PopPolicy/about_database.aspx).

United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (2006). Conference of European Statisticians Recommendations for the 2010 Censuses of Population and Housing. United Nations, Geneva.

United Nations Economic Commission for Europe and Eurostat (2010). Guidelines for Exchanging Data to Improve Emigration Statistics. Prepared by the Task Force on Measuring Emigration Using Data Collected by the Receiving Country. United Nations, Geneva.

![]()

1 The author would like to thank the National Statistical Offices of Armenia, Canada, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Spain, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom for providing additional data used in this report.